SMT profiling with Debian and perf

This article discusses profiling simultaneous multithreading (SMT) on the POWER9 architecture, using little-endian Debian with perf.

The knowledge presented here was derived from a variety of sources which can be found in the #Additional Resources section.

Contents

Simultaneous multithreading (SMT) principles

SMT is "multi-thread" not "multi-core"

This is an important distinction. SMT is a technology that increases throughput of instructions through parallelization where there are under-used CPU components. While SMT4 can support four threads per core and SMT8 can support eight threads per core, this is not an additional three and seven cores, respectively. There are trade-offs and benefits. Per-thread performance declines with increasing utilization of SMT levels, but overall performance and power consumption efficiency increase. An "eight core SMT4-capable system" will have eight cores and can execute up to 32 threads in SMT4 mode, or only eight threads in SMT1 mode. For tasks that can be parallelized, such as idle background daemons waking up or with pthreads to divide data analysis into segments, overall execution time will decrease. However, the performance of each thread in SMT4 mode will be slower than the performance of each thread in SMT1 mode, and the effect is non-linear. SMT4 will take more than 1/4 of the time it would have taken in SMT1 mode. The SMT mode during execution makes a difference on the overall performance. Note that IBM did not market SMT as "multi-core," while several media sites conflated SMT with increased core count.

SMT re-uses spare resources

Superficially, SMT re-uses over-provisioned resources to increase total throughput, at the expense of individual thread performance. For example, a POWER9 core provides

"Support for up to 40 predicted taken branches in-flight,STmode. Twenty predicted taken branches per thread in SMT2 mode and ten predicted taken branches per thread in SMT4 mode"

(page 31 POWER9 Performance Monitoring Unit User Guide v12).

Section 5.2 Partitioning of Resources in Different SMT Modes of the POWER9 Processor User's Manual (page 139) shows how different execution units are shared in different SMT modes.

This sharing allows for overall increased throughput, but not as if there were three additional cores. It's more like four people carrying eight bricks by hand each instead of one person moving forty at a time with a wheelbarrow. Over a given period of time, four people with lighter loads and moving faster will deliver more bricks, but the per-person average is lower. And the math in the analogy above is correct - some compromises are made to achieve the higher overall throughput.

For example, one important aspect to enabling this extra throughput is that instruction prefetching is turned off in SMT4 mode. Page 338 of the Power9 Processor User's Manual states

An instruction prefetch mechanism is used to fetch additional lines after an I-cache miss is detected. The instruction prefetcher uses the I-cache miss history to make decisions about the depth of prefetching on a per miss basis, ranging from 0 - 7 lines ahead. The mechanism is not active in SMT4 mode. The bandwidth of the instruction prefetcher is extended when the sibling core is inactive.

If there are two hundred bricks to be moved, four people carrying eight at a time are a faster option if they can do six trips in the time it takes one person to load a wheelbarrow and move it five times. However, that might not be the best way to do things when there are only twenty bricks to move and the four people have to wait to be told what to do next each trip because they can't look ahead. It's not four people with four wheelbarrows. It's one person with a wheelbarrow and a plan, or four people with two hands each but no plans. (It's just a superficial analogy to convey the concepts and dispel the "multi-core" myth erroneously attributed to SMT.)

Performance Monitor Counters (PMCs)

PMCs are essential for profiling your code. The full breadth of PMCs is beyond the scope of this article, but essentially they count everything. For example, if your code regularly accesses memory, PMCs can tell you how often each data cache has a miss and needs to load a pipeline, which will cause a stall. This might lead you to reorganizing your data. If you can't measure it, you can't objectively know if you are making improvements.

The POWER9 CPU has a vast number of countable events in the six PMCs ("The POWER9 core supports in excess of 1000 events," page 34 POWER9 Performance Monitoring Unit User Guide v12). Each SMT thread-core has a set of six PMCs. In SMT1 mode, each core has one set of PMCs, and in SMT4 mode they have four. In this article we will focus on measuring how often the cores are in SMT4 mode and the impact on performance.

Documentation on the POWER9 PMCs is at POWER9 Performance Monitoring Unit User Guide v12. Of particular note is the discussion of the POWER9 core and its functional units as discussed in Unit 4, and the organization of PMC events as discussed in Section 5.9, CPI Stack Events.

Operating Environment

Hardware

The bare metal hardware for Debian is an eight core SMT4-capable Talos II system.

# lscpu Architecture: ppc64le Byte Order: Little Endian CPU(s): 32 On-line CPU(s) list: 0-31 Model name: POWER9 (raw), altivec supported Model: 2.3 (pvr 004e 1203) Thread(s) per core: 4 Core(s) per socket: 8 Socket(s): 1 Frequency boost: enabled CPU(s) scaling MHz: 67% CPU max MHz: 3800.0000 CPU min MHz: 2166.0000 Caches (sum of all): L1d: 256 KiB (8 instances) L1i: 256 KiB (8 instances) NUMA: NUMA node(s): 1 NUMA node0 CPU(s): 0-31 Vulnerabilities: Gather data sampling: Not affected Indirect target selection: Not affected Itlb multihit: Not affected L1tf: Mitigation; RFI Flush, L1D private per thread Mds: Not affected Meltdown: Mitigation; RFI Flush, L1D private per thread Mmio stale data: Not affected Reg file data sampling: Not affected Retbleed: Not affected Spec rstack overflow: Not affected Spec store bypass: Mitigation; Kernel entry/exit barrier (eieio) Spectre v1: Mitigation; __user pointer sanitization, ori31 speculation barrier enabled Spectre v2: Mitigation; Software count cache flush (hardware accelerated), Software link stack flush Srbds: Not affected Tsx async abort: Not affected # lsmem RANGE SIZE STATE REMOVABLE BLOCK 0x0000000000000000-0x00000007ffffffff 32G online yes 0-31 Memory block size: 1G Total online memory: 32G Total offline memory: 0B # facter | grep virtual is_virtual => false virtual => physical

Debian identifies the hardware as having "32 cores." This is not correct; it is eight POWER9 CPUs with SMT4 capability.

Operating Systems

Two environments will be used for the operating environment. One is the bare metal systems as discussed above, and a QEMU VM to be discussed later, both of which runs Debian:

# uname -a Linux 93-224-155-23 6.1.0-37-powerpc64le #1 SMP Debian 6.1.140-1 (2025-05-22) ppc64le GNU/Linux

Profiling software

perf

perf is part of the package linux-perf. It does need to be run as root. "perf" is the overall front-end to the commands it orchestrates:

# perf --help usage: perf [--version] [--help] [OPTIONS] COMMAND [ARGS] The most commonly used perf commands are: annotate Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display annotated code archive Create archive with object files with build-ids found in perf.data file bench General framework for benchmark suites buildid-cache Manage build-id cache. buildid-list List the buildids in a perf.data file c2c Shared Data C2C/HITM Analyzer. config Get and set variables in a configuration file. daemon Run record sessions on background data Data file related processing diff Read perf.data files and display the differential profile evlist List the event names in a perf.data file ftrace simple wrapper for kernel's ftrace functionality inject Filter to augment the events stream with additional information iostat Show I/O performance metrics kallsyms Searches running kernel for symbols kmem Tool to trace/measure kernel memory properties kvm Tool to trace/measure kvm guest os kwork Tool to trace/measure kernel work properties (latencies) list List all symbolic event types lock Analyze lock events mem Profile memory accesses record Run a command and record its profile into perf.data report Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display the profile sched Tool to trace/measure scheduler properties (latencies) script Read perf.data (created by perf record) and display trace output stat Run a command and gather performance counter statistics test Runs sanity tests. timechart Tool to visualize total system behavior during a workload top System profiling tool. version display the version of perf binary probe Define new dynamic tracepoints trace strace inspired tool See 'perf help COMMAND' for more information on a specific command.

In addition to the 'perf help COMMAND' there is 'man perf', which will lead to other man pages:

#man perf

...

SEE ALSO

perf-stat(1), perf-top(1), perf-record(1), perf-report(1), perf-list(1)

'perf list' gives the PMC events that can be monitored:

# perf list List of pre-defined events (to be used in -e or -M): branch-instructions OR branches [Hardware event] branch-misses [Hardware event] cache-misses [Hardware event] cache-references [Hardware event] cpu-cycles OR cycles [Hardware event] instructions [Hardware event] stalled-cycles-backend OR idle-cycles-backend [Hardware event] stalled-cycles-frontend OR idle-cycles-frontend [Hardware event] ...

The default profiling is efficient. Using cmp_mp above, with a minimum length of twelve consecutive nucleotides and using eight threads with a silent output,

# perf stat ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 8 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766

min_pct_f = 1.00

min_len = 12

n_jobs = 8, map_size = 7441 (0x1d11), slice_mod 0, against_sz 29764

number of sequences: 225

longest sequence: 2848 ([19475, 19475), (22322, 22322)]

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_8_12_0_100_nuc.csv

Performance counter stats for './cmp_mp -l 12 -j 8 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1':

11,299.17 msec task-clock # 7.723 CPUs utilized

1,305 context-switches # 115.495 /sec

107 cpu-migrations # 9.470 /sec

129 page-faults # 11.417 /sec

42,267,506,274 cycles # 3.741 GHz (33.42%)

85,292,379 stalled-cycles-frontend # 0.20% frontend cycles idle (50.16%)

25,916,474,922 stalled-cycles-backend # 61.32% backend cycles idle (16.75%)

56,555,412,611 instructions # 1.34 insn per cycle

# 0.46 stalled cycles per insn (33.49%)

12,217,316,310 branches # 1.081 G/sec (50.07%)

758,041,604 branch-misses # 6.20% of all branches (16.56%)

1.463125416 seconds time elapsed

11.307016000 seconds user

0.001290000 seconds sys

It took 1.46 seconds to run the analysis, during which time slightly less than eight CPUs were fully utilized, with a measured 1.34 instructions per cycle.

perf record and perf annotate are two additional useful features. For production runs, cmp_mp is compiled without symbols, but for debugging it is. Using only a single thread with the debugger version,

# perf record ./cmp_mp_sym -l 12 -j 2 -T -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1 num args: 9 -l optarg = 12 multithreading disabled input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766 min_pct_f = 1.00 min_len = 12 n_jobs = 2, map_size = 29764 (0x7444), slice_mod 0, against_sz 29764 number of sequences: 222 longest sequence: 3270 ([19475, 19475), (22744, 22744)] file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_2_12_0_100_nuc.csv [ perf record: Woken up 6 times to write data ] [ perf record: Captured and wrote 1.724 MB perf.data (44906 samples) ]

This can be analyzed with perf annotate:

This immediately identifies two stalls; one ld (load doubleword) and one std (store doubleword), associated with the line of code

map->comparisons++;

A quick check of the code shows this is inside the comparison loop and so executes with every single comparison. This is a major bottleneck which can be addressed by altering from a memory-resident variable to a local (automatic) variable, with the final value copied to its destination. This changes the process from reading from and writing to memory to incrementing a register, of which there are plenty. Although not explored in this article, the said change resulted in a 12% gain in performance on four different RISC-based CPUs (SG2000, ARMv7, PowerPC G4, and POWER9), but cost 12% in performance on a CISC-based i7 (MacBook Pro). As it were, the C11 standard prevents compilers from making this optimization transparently, because the struct "map" might be altered in a different location. Therefore the programmer needs to know what hardware the code is running on in order to ensure maximum optimization. Perhaps this shall be discussed at another time...

Benchmark code

Description of comparison code (cmp_mp)

A lengthy description of the benchmark code is included in order to show the relevance of this workload. Unlike many benchmarks that test specific functions and might or might not highlight specific performance, this benchmark is a real-world, actual workload with high memory access on a byte-by-byte basis. You can skip ahead to #SMT profiling with Debian and perf if the details are not relevant to your needs.

The code being profiled and used for benchmarking is the genomic comparison code that the M. P. Janson Institute for Analytical Medicine uses to look for molecular mimicry between pathogens and human tissue and hormones. This code uses a variety of techniques to compare nucleotide and amino acid sequences. There are both byte-by-byte and vector versions. The raw source code can be found at TBD

Fundamentally the algorithm just compares characters in two sequences for matching. The goal is to match consecutive characters between two sequences with constantly changing characters, and record the string and location of the matches. Unlike strstr or similar functions, the string to be matched is not known in advance. The first character in one sequence is compared against the first character in the other sequence. If it matches, the second characters are compared. If they match, the third characters are compared, and so on, until the characters do not match. If the length of the matched string is below the minimum desired length, the match is discarded and the comparisons start over at the next character. This can "slide" the comparisons relative to each other, so if the first four characters match but not the fifth, the comparison starts over at the first character of one sequence and the fifth character of the other. If there is a match of sufficient length, that two-dimensional region is marked as an "exclusion region" and not searched again.

The code can run N number of user-specified pthreads in parallel (-j N), by slicing one of the two sequences into smaller pieces and stitching the results together. N must be an even number (one forward, one reverse). Some matches are lost at the boundaries between slices when one or both parts are less than the minimum length. The execution time is extremely sensitive to comparisons made; adding checks to determine if a match falls on a slice boundary adds significant overhead. For large sequences, the odds of a matching string falling on a boundary are very low; for small sequences, running fewer threads is effective without costing significant time delays. For absolute accuracy, run only two threads (one forward and one in reverse).

Description of data

(Skip ahead to #SMT profiling with Debian and perf)

Nucleotides are denoted as A, T, C, and G. There are three nucleotides in an amino acid, and 23 amino acids in humans, which leads to "isocodon" amino acids. These have the same function but different nucleotide combinations. There are amino acids that denote the initiation and termination of a gene. The amino acid is determined by its offset from the initiation amino acid (ATG, methionine), which starts an "Open Reading Frame (ORF)." ORFs can overlap. DNA has a forward ("sense") and backward ("anti-sense") direction, so there are three possible amino acids reading forward, and three when reading backwards. Nucleotide sequences are usually published in the forward direction, and the other strand's nucleotide matching the forward direction is inferred (A matches T, and C matches G, and vice versa). Genome sequences can be obtained from the NIH National Library of Medicine gene database, as well as in other places. The particular sequence is identified by its "accession number," and sequencing of the same organism by different labs does lead to different accession numbers. Some sequences are "canonical," meaning the generally accepted sequence that is often an assembly of accessions, and others are "contributions," meaning independently obtains sequences submitted for recording.

A typical "FASTA" file contains data as

TATATTAGAGTAGGAGCTAGAAAATCAGCACCTTTAATTGAATTGTGCGTGGATGAGGCTGGTTCTAAATCACCCATTCAGTACATCGATATCGGTAATTATACAGTT...

The most common comparison method is BLAST, which uses a database of pre-identified nucleotide sequences. This is useful for rapidly finding large matches, but does not offer granularity for exploring other aspects of the genome. The above method allows matching of nucleotide and amino acid sequences on both position one and position two nucleotide. This often reveals "repeat motifs" where a sequence of nucleotides is repeated multiple times within a pathogen. The current thinking is that this is an "immuno-evasive strategy," allowing the pathogen to escape detection by the host's immune system. Additionally, by recording the location of the matches, the distance between matches can be calculated. This is important in deciding if a host antibody would identify healthy tissue and hormones as pathogenic, by having similar shapes. The above algorithm also allows for detecting "SIDs," which are "Substitutions, Insertions, and Deletions," which occur regularly in rapidly evolving pathogens such as viruses.

For example, relative to the example above

TTATATTAGAGTAGGAGCTAGAAAATCAGCACCTTTAATTGAATTGTGCGTGGATGAGGCTGGTTCTAAATCACCCATTCAGTACATCGATATCGGTAATTATACAGTT...

is identical except for the inserted nucleotide T at the very first character. If the ORF is prior to the sequence above, this changes the amino acid structure by altering the anchor point for examining three nucleotides at a time (a "codon"). A straight matching of amino acids would miss this. The comparison code (cmp_mp) has the ability to shift each nucleotide sequence by none, one and two positions to catch insertions that alter the identifiable amino acids, and can match against the first character ("T" in "TAA") or the second nucleotide ("A" in "TAA"), which is more highly conserved across evolutionary pathways.

Sample output

(Skip ahead to #SMT profiling with Debian and perf)

The output is a csv file:

CVD_OM003364.1,CVD_OM002793.1,225,2848,29762,29762,1,1, 1,1,163,163,164, ...

The first line indicates the sequences compared, the number of matches, the longest match, the length of each sequence, and the presentation form, in this case a 1x1 image. The second line indicates a match was found from (1, 163) in one sequence and (1, 163) in the other, for a length of 164 characters, inclusive.

The csv file is run through some custom image generation code using libjpeg. An example of the processed data is below

The image shows matching sequences between two bacteria, B. burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease, and B. miyamotoi, a bacteria in the same Borrelia family. Matches are occurring in both the forward and reverse directions. In this particular case, the B. miyamotoi sequence was assembled from fragments in both the "sense" and "antisense" direction. This is an artifact of how PCR is done, but has to be considered when doing analysis. Running only forward matching can lead to missed matches (a "false negative"). This comparison is particularly important because some people will exhibit symptoms of Lyme disease but only test weakly positive or not at all for Lyme disease. This is known in science but not practiced in medicine, leading to erroneous conclusions about the cause of the patient's symptoms (see Borrelia miyamotoi infection leads to cross-reactive antibodies to the C6 peptide in mice and men).

The B. burgdefori sequence is 1,455,375 nucleotides long, and the B. miyamotoi sequence is 907,293 nucleotides long. Each nucleotide is compared at least once, and when there are partial matches too short to place the nucleotide into an exclusion region, it may be compared more than once. In this case, more than 2.6 trillion comparisons are made (one comparison is forward against forward, and one is forward against reverse; reverse against reverse is the same as forward against forward because of the inverse nucleotide arrangement of DNA). When searching human genes, the comparisons can be on the order of quadrillions (10^15) and take hours even on fast CPUs even with multi-core threading. Optimizing the comparison code saves time and power consumption, and is the focus of the profiling done below.

Baseline comparison

(Skip ahead to #SMT profiling with Debian and perf)

For these benchmarks, two different sequences of Epstein-Barr (EBV) and SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) virii will be used. EBV is the virus that causes mononucleosis, but is also closely associated with multiple sclerosis and has identifiable molecular mimicry sequences. SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, evolved from a coronavirus, as can be shown by a comparison of amino acids (nucleotide shifts of none for CRNA and one for Covid-19, anchor on second position, match initiation, termination and arginine amino acids):

The COVID-19 sequences, OM002793.1 and OM003364.1 are suitable for short duration benchmarks. The EBV sequences, KC207814.1 and NC_007605.1 (canonical), are for longer benchmarks in which slight performance gains are measured. Each pair member in the two pairs of sequences is nearly identical to the other, so when analysis of branch prediction for misses is needed, one from each pair can be compared against the other.

A typical comparison command looks like

./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 8 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

It is specifying a minimum length of 12 consecutive nucleotide matches and four forward slices and four reverse slices, with the two Covid-19 sequences. For benchmark clarity, the -s (silence) flag is set. The output for only two threads:

$ time ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 1 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

Number of jobs must be even; adding +1 to n_jobs

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766

min_pct_f = 1.00

min_len = 12

n_jobs = 2, map_size = 29764 (0x7444), slice_mod 0, against_sz 29764

number of sequences: 222

longest sequence: 3270 ([19475, 19475), (22744, 22744)]

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_2_12_0_100_nuc.csv

5.80 real 11.19 user 0.00 sys

This is the most accurate baseline comparison. With two threads, there are no slices. For absolute single-threaded execution, add -T to the flags.

To show the performance for additional threads, increase the number of jobs to the core count (4):

$ time ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 4 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766

min_pct_f = 1.00

min_len = 12

n_jobs = 4, map_size = 14882 (0x3a22), slice_mod 0, against_sz 29764

number of sequences: 223

longest sequence: 3270 ([19475, 19475), (22744, 22744)]

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_4_12_0_100_nuc.csv

2.91 real 11.21 user 0.00 sys

A change to -j 16, the maximum thread-core count, yields

$ time ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 16 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766

min_pct_f = 1.00

min_len = 12

n_jobs = 16, map_size = 3720 (0xe88), slice_mod 4, against_sz 29764

number of sequences: 226

longest sequence: 2845 ([19475, 19475), (22319, 22319)]

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_16_12_0_100_nuc.csv

1.05 real 15.39 user 0.03 sys

Notice the impact of slicing - there are more matching sequences, and the longest sequence is shorter.

There can be a minor performance benefit by double-loading the thread-core count:

$ time ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

o_st.st_size: 29766 , t_st.st_size: 29766

min_pct_f = 1.00

min_len = 12

n_jobs = 32, map_size = 1860 (0x744), slice_mod 4, against_sz 29764

thread[1] had no matches

number of sequences: 234

longest sequence: 1860 ([13020, 13020), (14879, 14879)]

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_32_12_0_100_nuc.csv

1.02 real 15.60 user 0.02 sys

Post-processing output:

For completeness, the EBV against EBV comparison:

It shows widely spread "repeat motifs" that are shared among different strains. The same (but different) sequences are found repeatedly within the whole organism's genomic sequence. The function of repeat motifs is not completely understood, but may provide a shape or sequence that helps evade host immune system responses. EBV is a member of the Herpes family, remains latent in B-cells, and can reactivate periodically, just like varicella zoster (Shingles/chickenpox) and oral and genital herpes simplex.

SMT profiling with Debian and perf

Baseline profiling

To establish a baseline, we will use the Debian OS on bare metal as described earlier, and to focus on the areas where SMT affects performance, we will use six specific events: instructions, cycles, L1-icache-prefetches, L1-dcache-prefetches, pm_run_cyc_st_mode, and pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode. This should cover stalls due to cache-misses and how often the cores are in SMT1 and SMT4 mode.

In perf, the -e flag specifies the events of interest, but can be listed together if separated by commas. Specifying any events with -e means all events to be studied have to be specified. perf stat also has a very nice feature, -r/--repeat N, which allows to repeating the profiled code N times and collecting the average values with variance. The following profiling uses -r 100 and includes seven events of interest:

# perf stat -e task-clock,instructions,cycles,L1-icache-prefetches,L1-dcache-prefetches,pm_run_cyc_st_mode,pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode -r 100 ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

num args: 8

-l optarg = 12

input/CVD_OM002793.1.fasta, input/CVD_OM003364.1.fasta

...

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_32_12_0_100_nuc.csv

Performance counter stats for './cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1' (100 runs):

21,446.21 msec task-clock # 30.779 CPUs utilized ( +- 0.02% )

56,941,217,151 instructions # 0.74 insn per cycle ( +- 0.02% ) (49.73%)

77,085,115,514 cycles # 3.610 GHz ( +- 0.02% ) (66.55%)

162,324 L1-icache-prefetches # 7.603 K/sec ( +- 0.52% ) (83.31%)

251,264 L1-dcache-prefetches # 11.768 K/sec ( +- 0.32% ) (67.09%)

55,370,664 pm_run_cyc_st_mode # 2.593 M/sec ( +- 13.46% ) (83.63%)

77,209,022,034 pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode # 3.616 G/sec ( +- 0.04% ) (33.05%)

0.69678 +- 0.00135 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.19% )

The inference is that with 100 samples, differences beyond the variances are highly likely to be real. Note that the instructions per cycle has dropped dramatically from the previous 1.34 to 0.74, while the task-clock went from 7.723 utilized CPUs to 30.779 CPUs. Also note that even though four times more threads were used in parallel, the elapsed time only dropped from 1.46s to 0.70s, a factor of 0.48, not 0.25.

The data below is from increasing the thread count on the benchmark comparison and recording the results.

Benchmarking prefetching and instructions per cycle

SMT4 turns off instruction cache prefetching. Page 338 of the POWER9 Processor User's Manual states

An instruction prefetch mechanism is used to fetch additional lines after an I-cache miss is detected. The instruction prefetcher uses the I-cache miss history to make decisions about the depth of prefetching on a per miss basis, ranging from 0 - 7 lines ahead. The mechanism is not active in SMT4 mode. The bandwidth of the instruction prefetcher is extended when the sibling core is inactive.

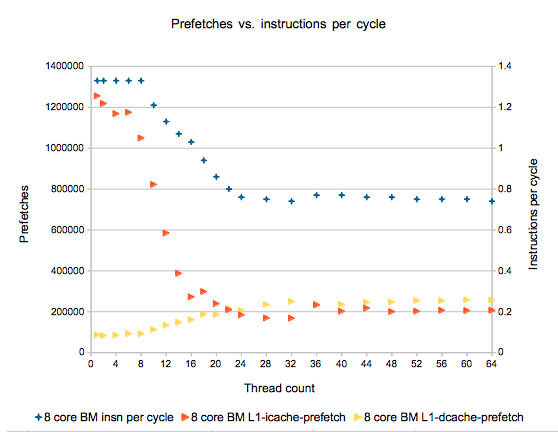

This can be seen in the graph below:

The instructions per cycle drop off in a beneficially non-linear response to decreases in prefetching instructions. During the benchmark run with less than eight threads being satisfied by remaining in SMT1 mode, the cores are executing on average 1.33 instructions per cycle (read on the right-hand y-axis), and approximately 1.2 million total i-cache prefetches (read on the left-hand axis). At 32 threads, instructions per cycle have dropped approximately 43%, to 0.74 instructions per cycle, while total i-cache prefetches have dropped by 86% to approximately 165,000.

Note that data cache prefetching actually increases with additional thread count, up to a maximum at 32 threads.

Below is the percent of time spent in SMT[1|2|4] mode on the 8 core bare metal machine as a function of thread count. The graph on the left shows the percent on a linear axis, while the graph on the right shows the percent on a log (base 10) axis. The log axis smooths out the drop in percent, but it is important to remember that the change in percent is non-linear. Zero is represented as "0.001" on the log scale, rather than omitted. Percentages were determined by using the total counts returned by pm_run_cyc_st_mode and pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode divided by the total cycles. In some cases >100% were calculated, but rounded down to 100%. SMT2 is inferred by 100-(% time in SMT1)-(% time in SMT4) since there is not a specific event counter for it.

As can be seen in the three graphs, there are distinct changes in modes at 8,16, and 32, corresponding to the necessity of transitioning from SMT1 to SMT2 at demands above eight threads, and against from SMT2 to SMT4 at demands above sixteen threads. There is not perfect 100% SMT1 usage below eight threads, due to scheduling of background processes.

Turning off and on SMT4

The package powerpc-ibm-utils has several useful components:

# apt info powerpc-ibm-utils Package: powerpc-ibm-utils Version: 1.3.10-2 Priority: important Section: utils Source: powerpc-utils Maintainer: John Paul Adrian Glaubitz <glaubitz@physik.fu-berlin.de> Installed-Size: 1,804 kB Depends: bash (>= 3), bc, libc6 (>= 2.34), libnuma1 (>= 2.0.11), librtas2 (>= 1.3.6), librtasevent2 (>= 1.3.6), zlib1g (>= 1:1.1.4) Suggests: ipmitool, sysfsutils Homepage: http://powerpc-utils.ozlabs.org/ Download-Size: 303 kB APT-Manual-Installed: yes APT-Sources: http://deb.debian.org/debian bookworm/main ppc64el Packages Description: utilities for maintenance of IBM PowerPC platforms The powerpc-ibm-utils package provides the utilities listed below which are intended for the maintenance of PowerPC platforms. Further documentation for each of the utilities is available from their respective man pages. . * nvram - NVRAM access utility * bootlist - boot configuration utility * ofpathname - translate logical device names to OF names * snap - system configuration snapshot * ppc64_cpu - cpu settings utility

Within ppc64_ppc is an ability to set the maximum SMT mode:

# ppc64_cpu --smt=1 # lscpu Architecture: ppc64le Byte Order: Little Endian CPU(s): 32 On-line CPU(s) list: 0,4,8,12,16,20,24,28 Off-line CPU(s) list: 1-3,5-7,9-11,13-15,17-19,21-23,25-27,29-31 ...

# ppc64_cpu --smt=4 # lscpu Architecture: ppc64le Byte Order: Little Endian CPU(s): 32 On-line CPU(s) list: 0-31 ...

Note the order of CPUs that go "offline" when SMT=1. This provides a hint into the scheduling of processes within the kernel (Linux-based Debian). This functionality is read-only on virtual machines; the actual host controls the real mode.

Altering the SMT mode allows for more profiling of SMT effects. For example, after setting SMT=2, the benchmark code with 32 threads runs

# ppc64_cpu --smt=2

# lscpu

Architecture: ppc64le

Byte Order: Little Endian

CPU(s): 32

On-line CPU(s) list: 0,1,4,5,8,9,12,13,16,17,20,21,24,25,28,29

Off-line CPU(s) list: 2,3,6,7,10,11,14,15,18,19,22,23,26,27,30,31

...

# perf stat -e instructions,cycles,L1-icache-prefetches,L1-dcache-prefetches,pm_run_cyc_st_mode,pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode -r 100 ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

...

Performance counter stats for './cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1' (100 runs):

57,106,151,065 instructions # 1.04 insn per cycle ( +- 0.02% ) (49.90%)

55,169,308,915 cycles ( +- 0.03% ) (66.57%)

363,832 L1-icache-prefetches ( +- 0.34% ) (83.30%)

178,460 L1-dcache-prefetches ( +- 0.30% ) (66.83%)

619,051,411 pm_run_cyc_st_mode ( +- 6.42% ) (83.39%)

0 pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode (33.39%)

0.99490 +- 0.00202 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.20% )

pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode shows zero cycles in SMT4, but 619,051,411 cycles in SMT1 mode is only 1.1% of the total cycles, justifying the previous inference that 100-SMT1-SMT2=SMT2 cycles.

Effects of SMT[1|2|4] on elapsed time and instructions per cycle

The effect of each SMT mode can be measured to obtain a clear picture of the performance gains that are available with having additional threads of lesser performance. For the tests below, the upper limit of SMT mode was set with ppc64_cpu.

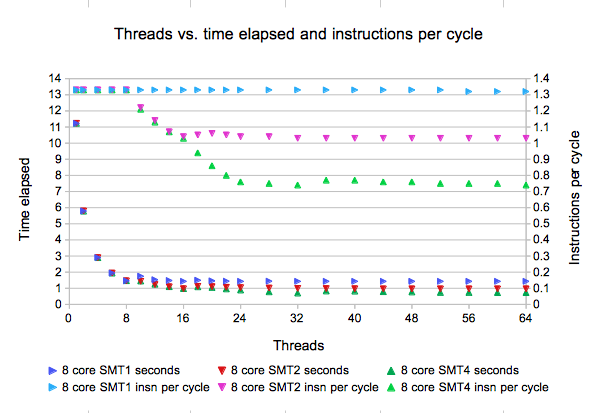

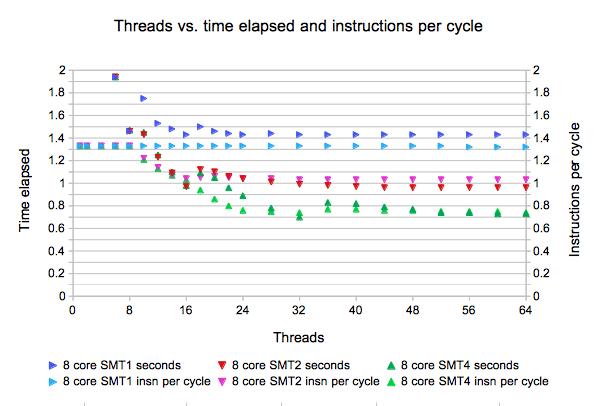

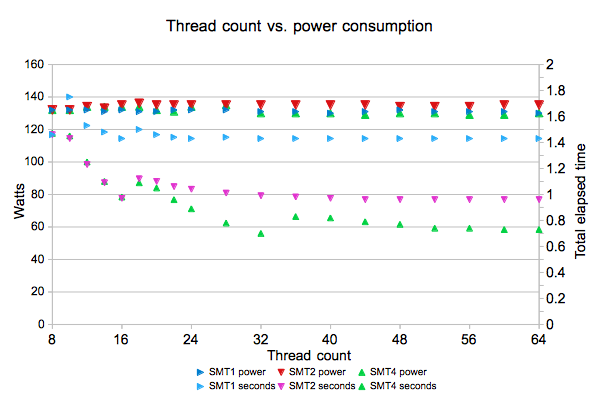

The two graphs above show the effects of increasing thread count at different SMT modes. The total elapsed time is on the left y-axis, while the instructions per cycle (across all threads) is on the right hand y-axis. The above two graphs are the same, except the bottom graph is cropped to 2 seconds total elapsed time.

The SMT modes have identical instructions per cycle, 1.33, through eight threads, which is the same as the core count. Once the thread count gets above the core count, additional overhead is incurred. In SMT1 mode, this means threads are switched in and out of a core. The instructions per cycle remains at 1.33, with a minimum elapsed time of 1.46 seconds. For SMT2 and SMT4 modes, at the expense of instruction prefetching and instructions per cycle, the symmetric multithreading capacity utilizes function units in parallel. For SMT2 mode, the minimum elapsed time is 0.97 seconds and 1.04 instructions per cycle, at 16 threads, or twice the core count. For SMT4 mode, the minimum elapsed time is 0.75 second and 0.7 second and 0.74 instructions per cycle, at 32 threads, or four times the core count. With all three modes, there are occasional improvements but in general the peak performance is at the mode times the core count.

| Metric | SMT1 | SMT2 | SMT4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lowest elapsed time | 1.46s | 0.97s | 0.70s |

| Instructions per cycle at best performance | 1.33 | 0.97 | 0.7 |

This is almost counter-intuitive. Fewer instructions per cycle resulted in lower total elapsed time. Recall that this is not a true "multi-core," where SMT4 means four cores. It is adding additional performance by utilizing parts of the core that are empty in SMT1 mode. More threads are being run, and therefore more throughput is obtained. It is not a perfectly linear gain, of course. The lowest elapsed time in SMT1 mode was 1.46 seconds, but 0.7 seconds on SMT4 mode, not 0.365 seconds if it were a true four core boost. This represents a 52% decrease in elapsed time, not a 75% decrease.

The second graph, on the bottom, highlights the proportionate gain in performance. By coincidence, the scales of the three modes converged when examining only eight cores and more. This shows a close correlation between fewer instructions per cycle but better performance overall.

Power consumption for SMT[1|2|4]

The obvious question becomes "Is this a free ride? What is the cost in energy for the additional 50% gain in performance?"

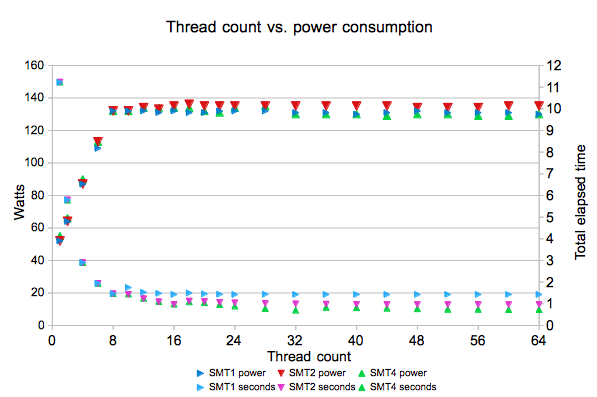

Power consumption can be measured through the internal sensor feature in Debian and the BMC sensors on the chassis. In this case, since some of the benchmark tests are so short, the very long benchmark of comparing EBV against chromsome 1 was used. This allows for a "steady-state" power measurement over a period of time. The bare metal machine was put into each of the three modes and the "most commonly noted" power consumption was recorded. This is not an exact average or mean quantitative analysis. The benchmark comparison would be initiated, the command 'sensors | grep W' would be executed several times during the run, and the BMC sensor would be refreshed repeatedly. If the number was consistently the same, fewer data samples would be taken, but more would be taken if variance or contrary results were noticed. The benchmark would be stopped, incremented to the next thread count, and initiated, while the results of the previous run were recorded. The sampling would start over.

Idle power consumption was measured at 32 watts. Maximum power consumption was measured at 130 watts.

The clear statement is that the power consumption increases linearly as additional cores are utilized, up to the maximum of eight, and that going into SMT2 and SMT4 do not cost significantly additional power. The nearly 50% decrease in elapsed time comes at a cost of only a few additional watts. This can be seen more clearly with a focused view showing only thread counts equal and greater than eight:

There is a small but measurable increase in power consumption with higher SMT modes, and more bounce in the variance. Above SMT mode level (i.e. 2X threads as thread-cores), the variance could be as high as seven watts, from a maximum of 136 watts to a low of 129 watts. This variance appeared to increase with an increase in SMT mode and the thread count, wherein the peak and low power consumption readings appeared equally as often. There were frequent thread count points where the power consumption noticeably bounced more, and even declined, with higher SMT modes and thread counts. Rather than conclude this is increased efficiency, it is possible this is greater inefficiency and the cores are idle more often during thread switching or other scheduler-related functions.

Of additional note is that the performance gain going from SMT1 to SMT2 is greater than going from SMT2 to SMT4. The power consumption appears to increase with SMT2 but decrease with SMT4. This bears further investigation at a later time.

Bare metal vs. Virtual Machines

Effects of host loads on SMT in client VMs

SMT mode is set by the host running virtual machines. To show an example of how this impacts the client VM, we will launch a QEMU VM with Debian and 1 core but four threads, and then load the host with a long benchmark that uses 30 threads. That still leaves two thread-cores for responsiveness.

The QEMU VM command:

# qemu-system-ppc64 --enable-kvm -nographic -M pseries,cap-nested-hv=true,cap-ibs=workaround -cpu host -smp cores=1,threads=4,sockets=1 -m 8G -nic user,ipv6=off,model=e1000,mac=52:54:98:76:54:32,hostfwd=tcp::2222-:22 debian.raw

The QEMU VM client:

# lscpu Architecture: ppc64le Byte Order: Little Endian CPU(s): 4 On-line CPU(s) list: 0-3 Model name: POWER9 (architected), altivec supported Model: 2.3 (pvr 004e 1203) Thread(s) per core: 4 Core(s) per socket: 1 Socket(s): 1 # uname -a Linux debian 6.1.0-37-powerpc64le #1 SMP Debian 6.1.140-1 (2025-05-22) ppc64le GNU/Linux

For the baseline on the client, we use a short benchmark (run 10 times):

# perf stat -e task-clock,instructions,cycles,L1-icache-prefetches,L1-dcache-prefetches,pm_run_cyc_st_mode,pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode -r 10 ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

...

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_32_12_0_100_nuc.csv

Performance counter stats for './cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1' (10 runs):

11,317.40 msec task-clock # 3.985 CPUs utilized ( +- 0.09% )

56,565,697,976 instructions # 1.33 insn per cycle ( +- 0.07% ) (49.81%)

42,562,384,883 cycles # 3.757 GHz ( +- 0.09% ) (66.73%)

1,556,239 L1-icache-prefetches # 137.357 K/sec ( +- 0.97% ) (83.45%)

394,039 L1-dcache-prefetches # 34.779 K/sec ( +- 1.62% ) (67.16%)

42,694,594,123 pm_run_cyc_st_mode # 3.768 G/sec ( +- 0.26% ) (83.61%)

289,256 pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode # 25.530 K/sec ( +-207.44% ) (33.08%)

2.84011 +- 0.00261 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.09% )

Notice that the 1.33 instructions per cycle is consistent with SMT1 mode, even though the number of threads consumed 800% of the client CPUs. Occasionally a core was put into SMT4 mode, but overwhelmingly the cores were in SMT1 mode. Now we load the host machine with a long benchmark:

# perf stat -e task-clock,instructions,cycles,L1-icache-prefetches,L1-dcache-prefetches,pm_run_cyc_st_mode,pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode -r 1 ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 30 -s chromosome_NC_000001.11 EBV_NC_007605.1

and rerun the benchmark on the client:

# perf stat -e task-clock,instructions,cycles,L1-icache-prefetches,L1-dcache-prefetches,pm_run_cyc_st_mode,pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode -r 10 ./cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1

...

file name: mp_CVD_OM003364.1_vs_CVD_OM002793.1_32_12_0_100_nuc.csv

Performance counter stats for './cmp_mp -l 12 -j 32 -s CVD_OM002793.1 CVD_OM003364.1' (10 runs):

21,689.29 msec task-clock # 4.009 CPUs utilized ( +- 0.11% )

56,755,363,259 instructions # 0.74 insn per cycle ( +- 0.04% ) (50.25%)

76,981,252,278 cycles # 3.566 GHz ( +- 0.07% ) (66.72%)

210,227 L1-icache-prefetches # 9.739 K/sec ( +- 6.18% ) (83.21%)

1,116,568 L1-dcache-prefetches # 51.724 K/sec ( +- 2.17% ) (66.64%)

0 pm_run_cyc_st_mode # 0.000 /sec (83.47%)

77,001,577,754 pm_run_cyc_smt4_mode # 3.567 G/sec ( +- 0.06% ) (33.47%)

5.41073 +- 0.00653 seconds time elapsed ( +- 0.12% )

Still only four CPUs utilized (with greater utilization), but the 0.74 instructions per cycle are reflective of the 100% running in SMT4 mode. The 5.4 seconds to complete the benchmark is comparable to an unloaded host running only two threads. However, this is coincidental, as even when the host was running 32 threads for the long comparison, the client executed the task in 5.4 seconds.

Conclusions

Managing SMT modes efficiently is a kernel-level task, but the programmer should know the management approach in order to maximize performance. Tools exist to lock processes to specific CPUs, although these were not examined in this article. It is key that the programmer understand that "simultaneous multi-thread" is not "multi-core." There are trade-offs for additional performance. SMT is a fascinating technology, and hopefully the reader has a greater understanding of it after reading this article and experimenting on their own.

Additional Resources

POWER9 Performance Monitoring Unit User Guide v12

POWER CPU Memory Affinity 3 - Scheduling processes to SMT and Virtual Processors

Wikipedia article on Simultaneous Multithreading

Developer access

Raptor Computing Systems supports many different development models from bare metal access (e.g. kernel hacking) through software development. If you are interested in developing with Debian and would like an account on our system, please email support@ this domain (raptorcs.com) with a description of your interests.